In our universe, whether as large as a galaxy or as small as an electron, we are always in motion, and even when we think we are sitting motionless in our chairs, the earth is carrying us around the sun at a speed of about 30 kilometres per second, and the sun is also in motion, in fact it is carrying the entire solar system around the centre of the milky way, and at a speed of about 220 kilometres per second.

A simple calculation shows that the solar system moves a distance of about 7 billion kilometres per year. It is puzzling that the solar system is always in motion, but the north star we see is always due north.

If we walk in an environment with an open field of view while observing a distant sight, then we will see that, despite the distance we have travelled, there is no change in the relative position of the distant sight to us in our eyes. In general, the further the scene is from us, or the shorter the distance we have moved, the more pronounced this phenomenon becomes.

Now let's look at polaris. The observations show that polaris is about 433 light years away from us, which translates to about 4 trillion kilometres, so you can see that the 7 billion kilometres the solar system moves every year is nothing compared to this distance.

In terms of the ratio between the two, it is as if a scene is 5.7 km away from us and we only move 1 cm per year. At this rate, even if we moved for 10,000 years, it would be difficult to observe a change in its position relative to us.

In the vastness of cosmic space, the solar system can be said to move more slowly than a snail, and it is only after a long period of time that the relative position of polaris, as seen from earth, changes significantly. In other words it means that polaris is not always due north, but only temporarily, and with time it will sooner or later leave due north.

So the question arises, if polaris were to leave due north one day, would the people of earth still call it polaris?

Of course not, because polaris actually means "The star closest to the north celestial pole", which we can simply understand to mean that the star pointing north on the earth's axis of rotation is polaris.

In other words, polaris is not the name of a particular star, and when the star we now call polaris leaves due north, then earthlings will again refer to the other star pointing north on the earth's axis of rotation as polaris.

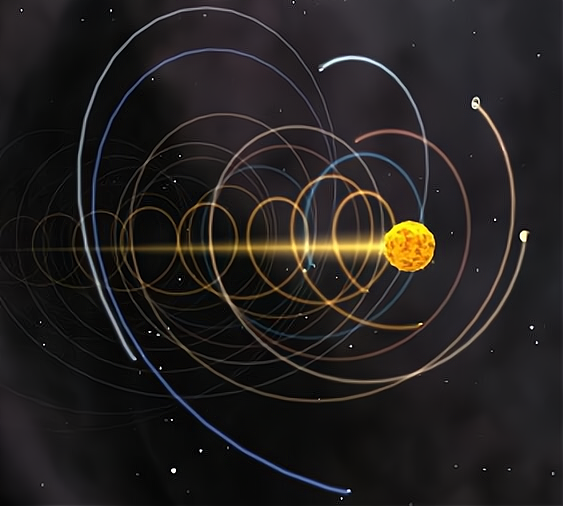

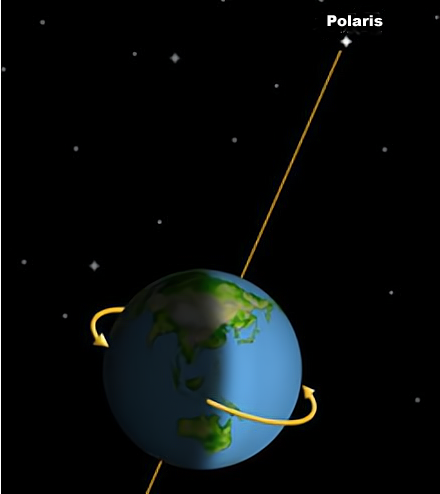

It is important to note that the earth's axis of rotation does not remain unchanged as we might think; according to astronomers, the earth's axis of rotation oscillates periodically under the gravitational pull of the sun and the moon, roughly like this.

This is known as 'earth-motion' and has a period of about 25,700 years, which changes the name polaris more rapidly than the solar system, which moves 7 billion kilometres per year. So which star will be the 'next' polaris? Let's see.

The current polaris is gou chen i, also known as alpha ursae minoris, which is currently approaching the north celestial pole and will reach its closest position in the next few decades, after which it will drift away from the north celestial pole and, in about in about 500 years, the nearest star to the north pole will be a star called gautam iv.

"Gou chen iv, also known as ξ ursae minoris (ξ is pronounced "Kesi"), has an apparent magnitude of 4.28 and is much less bright in the night sky than gou chen i, which has an apparent magnitude of 1.98. "In 3300 ad, the star will be "Shao wei zeng hao", and in 4400 ad, it will be "Shao wei zeng qi "......

The table above lists some of the stars that will be the future north star, and it can be seen that between 13500 and 14100 ad, the familiar star vega will also be the north star.

We on earth refer to the star directly north as polaris, and once it has left the north, it will no longer be polaris. The reason why we think that polaris is always due north is that the name polaris has been changing for too long for us humans.