Everything we can see in the universe has an internal structure and they are all made up of smaller matter, so what is the smallest matter in the universe?

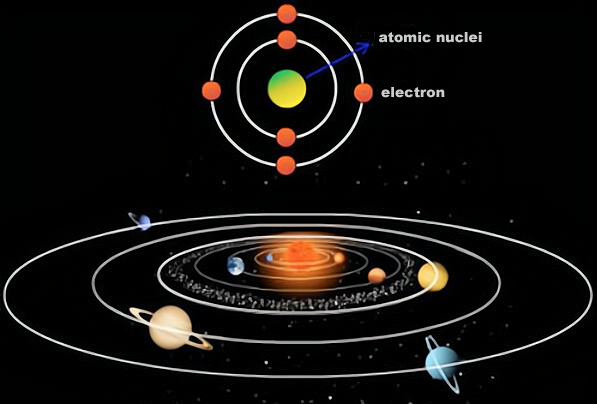

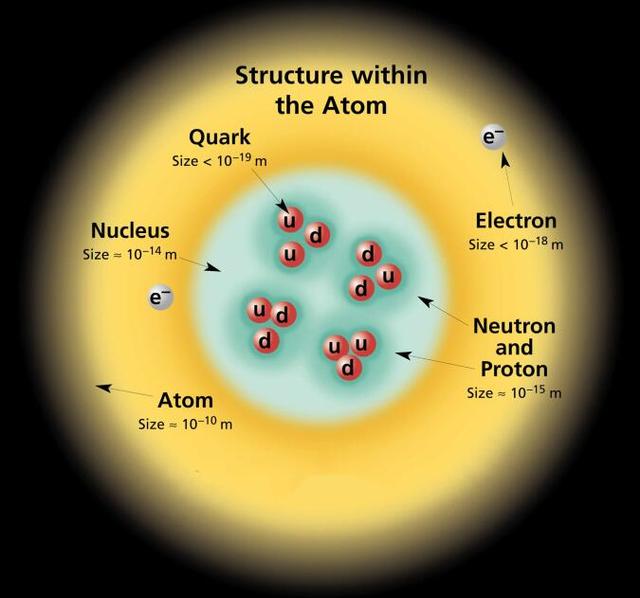

At first, it was thought that atoms were the smallest matter in the universe, but later physicists discovered that atoms are also made of smaller matter, namely protons, neutrons and electrons.

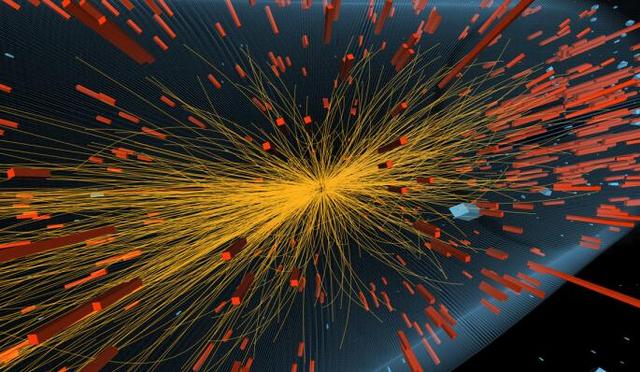

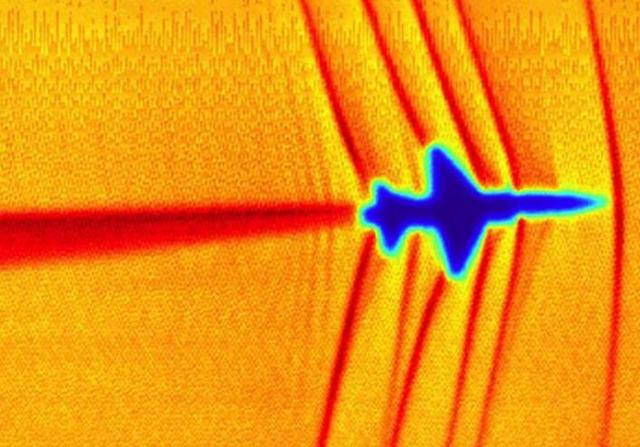

Then came the particle collider, a machine that accelerates microscopic particles to very high speeds (which can approach the speed of light) and then allows them to collide with each other, after which the microscopic particles may be broken up and we can then find smaller matter in these 'pieces'.

With this powerful tool, physicists have carried out a number of particle collision experiments, in which they have found a wide variety of particles, which, when classified, have led to a 'standard model of particle physics'.

These particles may seem confusing, but in fact they can be divided into three main groups, the first being "fermions", which include leptons and quarks, quarks that form "baryons" and "mesons" under strong interaction forces, and "The familiar protons and neutrons are in fact "baryons".

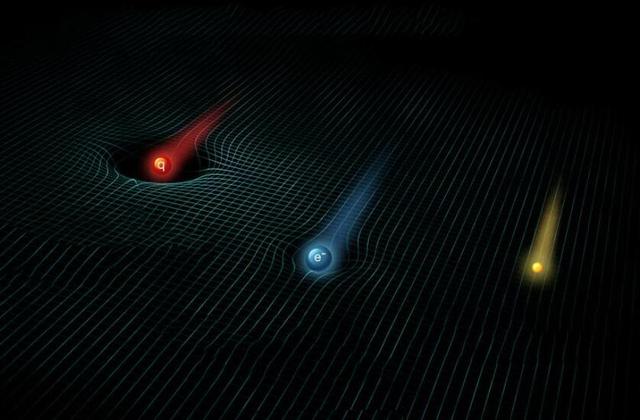

In simple terms, two up quarks and one down quark make a proton, while one up quark and two down quarks make a neutron. We know that protons and neutrons make up the nucleus of an atom, and that the nucleus of an atom plus electrons (a type of leptons) make up an atom, so that "fermions" are in fact the fundamental particles of matter.

The second group of particles is the "canonical bosons", whose role is to transmit interactions, with gluons transmitting strong interactions, photons transmitting electromagnetic forces, and "Z bosons" and "W bosons "Z bosons" and "W bosons" transmit the weak interaction force.

The "canonical boson" only transmits three of the four fundamental forces, but gravity is not one of them.

Physicists have speculated that there is a "graviton", a particle that is also a "canonical boson", and that it transmits gravity. So far, however, no evidence has been found for the existence of a "graviton", so there is an empty space here.

There is only one third type of particle, the Higgs boson, whose role is to give mass to other particles. Any particle that can interact with it is given mass (e.g. quarks and electrons), while particles that cannot interact with it do not have mass (e.g. photons).

In total, the Standard Model of particle physics contains 36 quarks, 12 leptons and 12 "canonical bosons", plus the Higgs boson, making a total of There are 61 elementary particles. Due to the limitations of technology, physicists currently do not have the experimental methods available to explore them in greater depth, which means that they are the smallest known matter in the universe.

Theoretically, these 61 elementary particles could be further divided into smaller structures, such as the "string theory", which suggests that the fundamental unit of everything in the universe should be a "string" of extremely small size, and that "The string can be either an open "open string" or a closed "closed string", and their different vibrations (or motions) give rise to a variety of elementary particles.

According to the "string theory", the size of a "string" can be as small as the Planck length, about 1.62 x 10^(-35) metres, which we can compare with the size of an atom.

The simplest atom in the universe is the hydrogen atom. The radius of a hydrogen atom in its ground state (lowest energy level) is about 0.528 x 10^(-10) m. That is, if we were to enlarge an object with a Planck length radius to the size of a hydrogen atom, its radius would be enlarged by a factor of 5.28 x 10^24.

The standard radius of a ping-pong ball is known to be 20 mm, so if we were to enlarge it by the same proportion, the radius of a ping-pong ball would be enlarged to about 11,162,000 light-years, which would be larger than the diameter of the "home galaxy group" in which our galaxy is located.

So we can clearly see how small a "string" really is, and is there any matter smaller than a "string"? Sorry, but the Planck length is the smallest unit of distance in physical terms, and this is the limit of physics. Therefore, if the "string theory" is valid, the smallest matter in the universe is a "string", and it is physically pointless to discuss matter smaller than a "string". There is no point in discussing matter smaller than a string.